What can we learn from Afghanistan for development aid projects around the globe?

Most of us were shocked about the speed with which the Taliban reconquered Afghanistan in August, after international troops ended their operations in the country. While some might not have been surprised by the come-back of the group, most of us might not have expected that it would happen so fast. And many of us were probably even more shocked by the pictures of despair that went through the web during the days after the Taliban’s invasion in Kabul. The fear of the people who had cooperated during up to two decades with Western nations was heart-breaking. Many saw themselves forced to flee their beloved country or to go into hiding. A lot of NGOs and development aid workers started to say that the progress made during nearly 20 years, especially in the area of gender equality, was destroyed in just a couple of days. So – what can we learn from what has happened in Afghanistan for future development projects around the world? Is it all in vain?

Weak governance as one of the main risk factors to development aid

In a speech president Biden gave by the end of August, he stated that the assumption behind the end of military operations was that 300,000 Afghan National Security Forces soldiers would take over in the civil war with the Taliban. But the Afghan president was among the first ones to flee the country, and there are some reports about him leaving with cars and a helicopter full of money (Reuters). This might be a nice image of the underlying problems Afghanistan’s state bodies have been facing since 2001. There were numerous and continuous reports about problems of corruption and weak governance in the country. Some even said that the levels of corruption were endemic and swiped the entire Afghan public sector (U4).

In fact, Afghanistan ranked on the 165th place out of 180 countries on the Corruption Perception Index in 2020. And the low performance of the public sector in the country does not become any better when looking at alternative indicators measuring the strength of the government. In fact, in a policy brief we wrote recently, we found that the country is among the weakest performers on a variety of indicators measuring the performance of its public sector as its control of corruption, rule of law, regulatory quality, political stability and accountability (Albrecht et al. (2021). Foto by Mohammad Rahmani

Having this in mind, is it really a surprise that the government in Afghanistan showed so little resistance to the Taliban’s invasion? Our first learning from Afghanistan should be that we can never underestimate the political economy behind development aid projects. This is actually something that a lot of development projects in many developing countries have to deal with: Weak governance. While many aid projects nowadays try to introduce mechanisms directed at aid effectiveness, good governance and corruption control, there is still a long way to go (Brookings). Aid agencies continue to pump large amounts of money into corrupt government accounts and the control mechanisms are far from perfect. There are some agencies that even go more along the line that governance is not their area of expertise and nothing they can intervene with. But how can we design effective development projects without taking one of the biggest risks for these projects into account, which indeed is weak governance? In fact, several reports conducted on aid effectiveness in Afghanistan showed that it is low and ineffective (see for example this summary by the Afghanistan Analyst Network).

Aid dependency and aid effectiveness

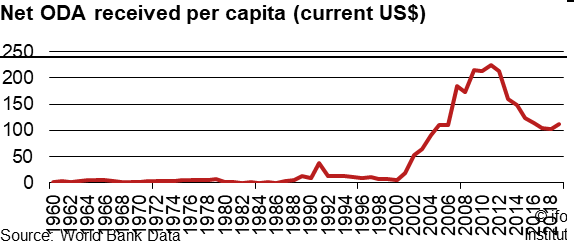

This brings me to my next point: Aid dependency and aid effectiveness. Many academic scholars and analysts have pointed out the high aid-dependency in Afghanistan during the last decades (Karimi 2020). The net official development assistance (ODA) per capita was 6.5 current US-Dollar in 2000 and 224.0 current US-Dollar in 2011 (see the figure below). In 2019 the ODA per capita was 113 US-Dollar, which is 16 times higher than the average per capita ODA for lower middle-income countries and 1.5 times higher than the one for low-income countries. It made up for a large share of the central government expenses (more than half of it in 2017 compared to 200 percent in 2006) (World Bank, 2021). Aid dependency might have led to the formation of a parallel public sector with four-fifth of total foreign aid spent outside the government (Karimi 2020). It might also have led to state fragmentation, corruption, fiscal instability and decreases in social trust as well as the formation of a war-aid economy (Karimi 2020). A 2018 report finds that aid ownership by state bodies was low (ATR Consulting 2018). It also came to the conclusion that aid effectiveness in the country is low.

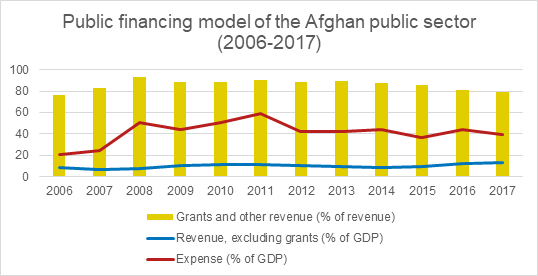

Additionally, the government’s public financing model has been unsustainable and subject to a difficulty to raise domestic funds (see the figure below). Afghanistan has been facing challenges to develop a sustainable public financing model since 2001 (Karimi 2020). The difficult labor market situation comes hand in hand with low tax revenues for the government. Tax revenue was low, fluctuating between 5 and 10 percent of GDP between 2006 and 2017 (World Bank 2021). Institutional weaknesses further added to the difficulty to raise domestic resources. The graph below shows that there has been a constant dependency on grants which made up for more than 75 percent of revenues between 2006 and 2017 (World Bank 2021). Additionally, public expenses have constantly been higher than public revenues. This was mainly due to high security spending in the country. While Afghanistan spends 30 percent of its GDP on security, this is only 3 percent on average in low-income countries (World Bank 2019).

Now, with the Taliban taking over, most countries have blocked their financial support to the country. One example is Germany, which had reserved around 300 million US-Dollar for the country and announced a complete halt of these transfers shortly after the Taliban seizing power. The effects on the local population and the ones most in need could be devastating. It has also led to a near still stand of the financial sector, as a large share of the Central Bank’s money is stored abroad (Albrecht et al.).

Our second learning from Afghanistan should be about sustainability and self-sustainability of development aid. When we design projects or start initiatives in development countries, we have to take a critical stand on what we are constructing. We should take the time to think about if the money really goes where we want it to go. We also have to ask ourselves what happens if the project-money runs out. Will the population the project is targeting still benefit from it? Or will the money just run out and everything goes back to normal? And if the answer to this is yes, then it might be better to redirect funds towards investing in the education and health of the people, in order to hand them the basic toolkits needed for creating self-sustainable projects themselves. I remember a conversation I had with a Paraguayan government employee during one of my field trips in the country. He said that development aid projects were all nice and beautiful, but that the biggest challenge in his opinion, after decades of having worked on them in different roles, was sustainability. According to his experience, initiatives always died off as soon as they ran out of project-money. So, let’s think out of the box and increase or knowledge on self-sustainable project management and design.

The stickiness of social norms

There is a saying which is that social norms are sticky. The role of social norms have increasingly started to play a role in research focusing on gender inequality and ways to break with it. The underlying rational is that it is not easy to change the minds of people and the ways in which they view the world around them. A typical example is the belief that women should not work. Nearly every third men on this planet is actually still convinced of that (Fortune). Afghanistan is known for being one of the places with the most marked gender roles in the world. In Afghanistan, only 15 percent of men think that women should work outside of their home (Brookings).

Social norms can result quite problematic for development aid projects. I remember that this was the case in Paraguay with respect to gender norms. Due to cultural traditions, land ownership was often in the name of the husband and not the wife. That makes it then difficult for women to access loans or even grants, as banks often require land ownership as collateral. But changing the way people think about this is not something you can do from one day to the other. Generations of Paraguayans were convinced of the fact that land should be in the name of men and not women. Suddenly telling them otherwise will probably be quite ineffective.

This and similar challenges have also emerged in Afghanistan. Not only do most of Afghan men think that women should not work. Also do they think that Afghan women had way too many rights by 2020 (Brookings). An analysis by SIGAR from early this year finds that social norms and insecurity are the largest barriers to gender equality in the country and that development aid projects have fallen short on fully understanding the limitations and challenges Afghan women and girls face in the country. Still, since 2001 there had been a shift due to the population’s exposure to the media, internet, mobile phones, foreigners and targeted development aid projects as well as reforms. Afghan women and girls have achieved significant gains on a variety of dimensions, such as in their access to education, health, political participation, access to justice and economic participation. Foto by Isaak Alexandre Karslian

Many NGOs state that we are now back to square 1 with respect to gender equality in Afghanistan. While there might be a new generation of women and girls which are more emancipated and stronger by now, the fear of the Taliban is great. And not only this – the Taliban might create an environment under which many of the conservative gender norms present in the country can flourish. So, the third take-away is about the importance of social norms. How much can we really change and influence? We should factor in these norms when designing projects and interventions and understand how powerful they are. Let’s keep in mind that they are also important drivers behind the sustainability of development aid.

Three lessons from Afghanistan

Summing up – what can we learn from Afghanistan? What we can learn is that we might need a paradigm shift when thinking about development aid. Yes, we will always need development aid flows financing the immediate needs of people suffering from hunger and health problems, as is also very visible in Afghanistan right now. But besides that, we need a shift away from traditional aid projects which often have a live of 5 years and then die off. We also need to be more careful about where the money we pump into developing countries is going and in designing mechanisms that assure a greater aid effectiveness. We have to take into account the governance factor behind the equation and realize that it is one of the largest risks to the success of these projects. And we need to focus more on the actual target population and self-sustainability of projects. Only if we hand over the adequate tools to create a self-sustained life, development aid will be truly effective. We also have to factor in the underlying social norms and think about interventions which foster social norms creating a better life for the people living under them.

So, does Afghanistan tell us that it is all in vain? For sure not. But we have to be more careful, more creative and more innovative in our approaches. We have to take more time in designing our programs and work hand in hand and very closely with the local population. Let’s try to move away from projects which are bureaucratic and static and try to find solutions which create a direct channel towards those who are most in need. And let’s never assume that, when we come in as outsiders, we know what these needs really are and that we bring along the perfect solution.