What has the pandemic taught us about inequality?

In times of crisis, the most vulnerable are the ones most affected

Since the start of the pandemic, U.S. billionaires have gained an additional 1 trillion US-Dollar (Statista). This is an increase of more than 34 percent since March 2020. At the same time, The World Bank estimates that the pandemic pushed 88 million to 115 million people into extreme poverty in 2020, a figure that could rise to 150 million in 2021. This gives a taste of the long-run economic impact of the pandemic on inequality, but runs short on the overall effect the pandemic has on the most vulnerable populations. What has the pandemic taught us about inequality? It has drawn a clear picture of what multidimensional poverty really means.

A health crisis: The developing world and its health system

When the pandemic hit South America in mid-March this year, Latin American governments reacted immediately, implementing strict and long lockdowns. This came as a surprise to some people as there were still relatively little cases. But the health infrastructure in the developing world lags behind the one in the developed world. Let’s have a look at three numbers that can give us a taste of that:

-

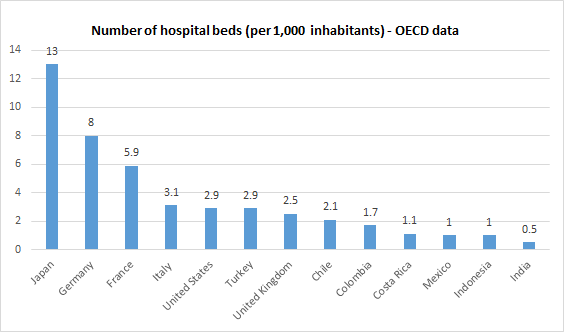

While Japan has 13 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants and Germany 8 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants, there are only 1.7 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants in Colombia, 1.1 in Costa Rica, 1.0 in Mexico and a stunning 0.5 in India (OECD).

-

When looking at more complicated health technology, as the number of x-ray machines, the discrepancy becomes even more evident. While the US has 45 x-ray machines per 1 Mio inhabitants, Colombia has 1. While Switzerland has 40, Mexico has 6 (OECD).

-

One can go even broader and look at current health expenditure per capita (in current international US-Dollar). While the Dem. Rep. of Congo spends 30.72 US-Dollar per capita on health, Afghanistan spends 186.41 US-Dollar per capita and Peru 766.64 US-Dollar. On the contrary, high-income countries spend on average 5.971 US-Dollar per capita on health, with the US leading the list (10.623 US-Dollar).

This data makes clear that the poor are less prepared to confront a global health crisis, as the COVID-19 pandemic. In the beginning of the crisis this led to a complete collapse of the health system in the Guayaquil area in Ecuador, and dead bodies lying on the streets (El Periodico). In addition to that, the poorest often live in poor neighborhoods, lacking sanitation as well as space to implement social distancing, or hygiene measures.

An economic crisis: Economic slowdown, liquidity and an increased debt burden.

Why is public spending important in times of crisis? The government response is necessary to mitigate the pandemic-induced financial and economic crises, and to avoid a collapse of the financial system as well as secure a rapid recovery and protect workers from job and wage losses.

In the beginning of the pandemic, Germany launched its largest aid package in its history (1.500 billion Euros) with the aim to cushion the negative economic effects of the pandemic. A total of 800 billion Euros was dedicated for federal and state guarantees to protect businesses and workers from the economic slowdown. Another 40 billion Euros went in the form of direct grants to small and medium-sized firms, trying to avoid insolvencies. Then there is a stabilization fund of 120 billion Euros to speed up and modernize Germany’s economy and infrastructure in the long run. Additionally, a total of 23 billion Euros goes to Germany’s so-called short-time work scheme, an instrument to protect employee’s from job or wage loss (Source). In March 2020, the US passed an over 2 trillion US-Dollar economic relief package, including cash and assistance for regular Americans, businesses, airlines and manufacturers (CNN). The United States has just passed a second aid package of 900 billion US-$, securing unemployment benefits for 14 million Americans (BBC). It includes a payment of 600 US-Dollar to Americans which earn less than 75,000 US-Dollar per year.

What happened in the developing world? When the pandemic hit the developing world, its request for fast liquidity increased immensely. The needs of developing countries are much more basic, leading from the purchase of masks, ventilators, medical equipment, intensive care units to food and cash necessary to cover the economic fallouts experienced by its populations. There was an urgent need to help the most vulnerable and poorest. The IMF gives an overview of the different government responses to the pandemic here. They reach from distributing bread in Afghanistan over an employment promotion program in Albania, to direct cash transfers in Argentina.

The United States has a GDP per capita of 65,297 US-Dollar (PPP) in 2019, and Germany of 56,278 US-Dollar (PPP). Sub-Saharan Africa, on the contrary, has - on average - a GDP per capita of 3,930 US-Dollar (PPP) and South Asia of 6,500 US-Dollar (PPP). The Arab World has, on average, a GDP per capita of 15,256 US-Dollar (PPP) and Latin America & Caribbean, on average, 16,890 US-Dollar.

So, it is pretty obvious that states forming part of the latter regions cannot respond with the same measures as Germany or the US. Additionally, even before the pandemic, almost half of all low-income countries were already facing debt distress (The World Bank), leading to less fiscal resources available for a direct and tailored response as described above for the US and Germany. The pandemic will increase the debt dependency experienced by low-income countries and therefore hinder rapid and sustainable growth after the pandemic. This, partnered with less fiscal resources, less business opportunities and jobs, as well as worsened living conditions might increase inequality between the developed and developing world in the long run, increase brain-drain and migration streams.

Social distancing: When working on the forefront of COVID-19

Poor populations often do not have the luxury to work from home, and benefit from lockdowns. Moreover, they often work on the forefront of COVID-19, working in low-skilled occupations, such as cleaning, security, retail, social and health care, transport, agriculture as well as manufacturing. Additionally, they often work in the informal sector.

Let’s take the bus driver in Buenos Aires, who lives in the poor neighborhood Villa 13, with approximately 30,000 to 40,000 inhabitants. He probably lives in a small place, sharing his space with his children, wife, parents, and maybe even siblings, edge to edge with his neighbors. Probably he also lacks access to the right sanitation, or the money for masks and regular hand-washing. Is it possible for him to implement social distancing? Or what about the empleada doméstica (housekeeper) who lives in Aguablanca, a poor neighborhood in Cali, Colombia with more than 700,000 people below the poverty line. Probably the demand for housekeeping has declined in the pandemic, resulting in a decline of work hours and income. Being an informal worker, it is also more difficult for her to access the social protection system. Another example is the agricultural sector. Imagine working on the crop fields in Paraguay, cultivating soya, corn, or vegetables. Can you stay home when cultivating crops, or livestock? But you don’t even have to go that far. Maybe you have strolled the beaches of Spain, Italy or Portugal and met its famous street vendors. These street vendors are often informal workers, or even undocumented, and not registered with any social protection agency.

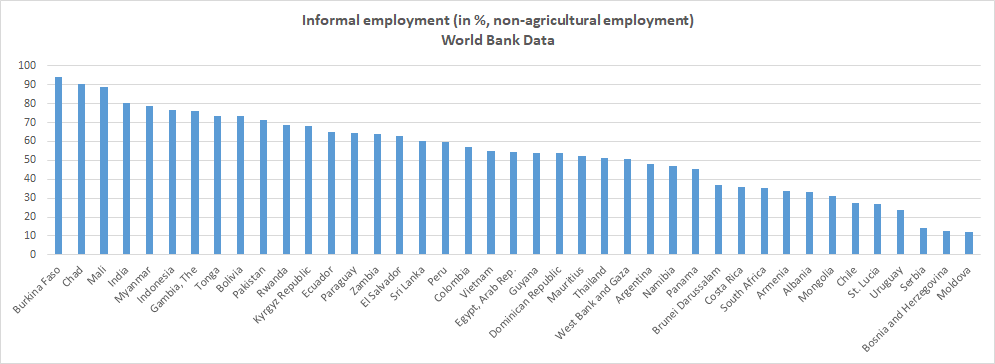

More than 30 percent of employees are informal in Albania, South Africa, Costa Rica and Brazil. More than 50 percent in Thailand, Colombia and Vietnam. And more than 60 percent in Mexico, Paraguay and Ecuador. In Bolivia, India and Uganda more than three quarter of all employees are informally employed. There are estimates that there are 2 billion informal workers worldwide, and that 1.6 billion of them might have lost their labor income due to the pandemic (Source).

This means that they fall out of the social protection system, not receiving any health insurance or social protection services. They are not registered with any government entity. As a consequence, when election criterias for government aid are designed, they are often not being considered. Sometimes, informal workers are also called the invisible poor. In times of crisis, the vulnerability that informality creates becomes evident. During the pandemic it became more evident than ever before, as these workers were affected by their double vulnerability: Not forming part of any official health system, nor forming part of the social protection system. This leads to them being on the frontline of the pandemic.

Additionally, developing countries depend more on industries most affected by the pandemic and benefit less from technological change and digitalization. 22.1 of value added as percent of GDP in low income countries is generated in the agriculture, forestry, and fishing industry, compared to 1.4 percent in OECD member countries. Even when looking at this on a country-by-country perspective, you will see that those industries most hit by the pandemic are those occupied by people forming part of the lower income percentiles, as tourism, restaurants and bars, laundry & other personal services or retail (Source). This will also lead to an increase of inequality within countries, too.

The fourth industrial revolution and COVID-19

One thing that has helped to mitigate the impact of the pandemic was digitalization, making it possible for thousands of workers to work under social distancing measures, and for lots of students to attend school on a home-based basis. But developing countries and poorer populations have less access to digital infrastructure as the richer populations. Let’s have a look at internet access, for example. Only one percent of people in Eritrea are using the internet, 17 percent in Pakistan, and in Kenya 23 percent. On average, 18 percent of people in low-income countries have access to internet, compared to 84 percent in Europe and 88 percent in North America. The digital adoption index for businesses by the World Bank is 0.86 for Germany, but only 0.6 for Peru and 0.29 for Liberia.

Another problem is home schooling. UNICEF estimates that two thirds of the world’s school-age children have no internet access at home (Source). As a consequence, the learning gap between poorer and richer children will increase in the long-run, leading to even larger gaps in human capital development. As a side effect, poor children have less access to school meals and nutrition, reinforcing the downward spiral of human capital development.

In times of crisis, the most vulnerable are the ones most affected

So what has the pandemic taught us about inequality? It has shown in a clearer and more direct way than ever before, thanks to a more connected and digital world, that the most vulnerable are the ones hit hardest in times of crisis. It has shown what multidimensional poverty really means, that poverty is not just about a lack of financial resources, a difference in money, but is much more structural than that. It is not just an income gap, but a health gap, digital gap, learning gap, human capital gap, a gap in opportunities and safety, and a visibility gap. Inequality will continue to grow in the long run, if we do not react now and take responsibility.